“It seems that many executives continue to make decisions not only based on the past but even in the interest of the past or in its defence,” writes Dr Morne Mostert, Director of the Institute for Futures Research at Stellenbosch University. According to him, “the intellectual agility to engage simultaneously with multiple possible futures is highly likely to increase as a prerequisite for a chair in the boardroom of the future”.

Executives often have good insights, but incessant change, talent deficits, rising complexity, compressed time-horizons and raging stakeholder demands with globalised interests have all contributed to an intellectual tax on those with executive accountability for their portfolios and organisations. That responsibility is, self-evidently, for a future state. To navigate towards that future state, requires advanced anticipatory abilities for high quality decision-making.

In a certain sense, all decisions may be seen as futures thinking, since no decision can be made for any other time. Despite the glaring, indisputable veracity of this observation, it seems that many executives continue to make decisions not only based on the past but even in the interest of the past or in its defence.

As executives rise in seniority, the quality of their decision-making becomes ever-more central to their effectiveness. Moreover, the nature of their technical competence is often inverted to their seniority. This is not to suggest that they require less technical know-how, but simply that the nature of their technical competence mutates with seniority to a more macro-perspective, characterised by knowledge of cycles, patterns and meta-perspectives, in addition to the integration of their technical field into the ever-broadening fields of expertise of others, including peers, direct reports and seniors.

In addition to the evolution in the nature of their technical competence, seniority also implies an expansion of their relational abilities: they must persuade, influence and build ever-growing networks of convergence. They must lead, motivate and inspire those around them to take on gargantuan challenges and believe in their cause.

As networks grow, so does the level of complexity of decision-making within them. This means that executives face tremendous intellectual demands. One trend over the last few decades as businesses left behind a more industrial approach and mind-set, is that the executive's tools have become dramatically less tangible. Issues such as customer loyalty, staff motivation, goodwill, management engagement levels and brand equity have been added to more traditional considerations such as capex budgeting and hardware maintenance. The ability, therefore, to engage meaningfully with concepts that have decreased in tangibility and measurability, requires that their cognitive processing (the methodology by which they think and make decisions) needs to be at the highest possible levels for strategic competitiveness.

Such networks further act as sensors of their environment, which may contain several opportunities and risks. These may be present not only in the immediate environment and current planning cycles, but also in the long-term and contextual environments.

Such networks further act as sensors of their environment, which may contain several opportunities and risks. These may be present not only in the immediate environment and current planning cycles, but also in the long-term and contextual environments.

For this reason, contextual intelligence (the awareness and navigation of non-immediate factors that are relevant and potentially subject to influence) has increased dramatically as a critical determinant for executive success.

It is in the interchange of relational, conceptual and contextual competence that the ability to navigate the future emerges as essential for the senior executive. As executives grow in their careers, the maturation date of many of their decisions is extended and evidence of the validity of their decision-making is postponed, sometimes for several years. Consider, for example, that an executive decision for a merger or acquisition only proves its worth over multiple budget cycles, while technical challenges of more junior staff can be tested almost immediately. For that reason, executive decision-making reaches far into the future for both the organisation and its community of stakeholders, thus strengthening the case for the enhancement of the quality of those decisions.

The ability to navigate the future has therefore also developed strategic relevance. Far from concerning itself with prediction and implying a type of clairvoyance, futures thinking examines the ability to anticipate a range of possible futures. It requires the ability to discern from the broad realm of possibility those futures that may be more plausible. This set is often simply a first indication of likelihood and should be tested by what is probable. By the latter is meant a more considered, well-argued and evidence-tested case, based on a set of assumptions.

But this introduces a classical dilemma for futures thinking, namely the source data for decision-making. If the futurist is concerned with a time yet to come, then from which time is the data drawn? The obvious implication is that evidence from the past (as all investment vehicles warn) is by no means an indication of the future. It is at this juncture that Preferability enters the fray.

This suggests that all organisations and the executives who represent them have an explicit or tacit desire for a particular future state. Said desire is expressed in the form of decision-making.

This can easily be proven by showing that not all executives in the same industry will make the same decision. The difference in their decisions can, at least partially, be explained by their different schemas (the totality of their unique histories) and their distinct expectations for what the future should hold in their view.

But the unique desirability of a future must always be contextualised by the range of possible futures, because for the futurist, more than one future is always possible, despite any evidence from the past or even present. This perspective requires the unusual marriage of intellectual humility and courageous decision-making, since not making a decision patently constitutes a decision by default.

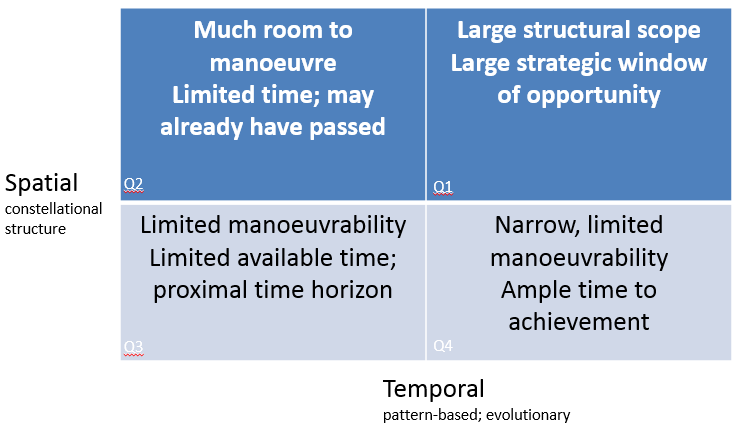

One way in which the range of possible futures may be navigated is simply to evaluate alternative futures. As seen in the diagram, the strategic executive may examine the spatial room to manoeuvre in relation to the time available to exercise a particular course of action before the strategic benefit expires.

One way in which the range of possible futures may be navigated is simply to evaluate alternative futures. As seen in the diagram, the strategic executive may examine the spatial room to manoeuvre in relation to the time available to exercise a particular course of action before the strategic benefit expires.

In Quadrant (Q)3, the executive takes the view that there is limited room to manoeuvre, and that time constraints further render the strategic option negligible.

In Q4, the view is taken that, despite structural constraints (such as legislation), there is ample time to conceive of and execute a workable strategy.

Q2 suggests that time is weighing heavily on the options available for decision-making, but that strategic options abound if the time compression factors could be overcome.

Q1 indicates a highly desirable strategic landscape, in which the spectrum of strategic options is broad and the time for achievement is ample. In this quadrant, the next strategic step might be to explore a-symmetry in favour of the executive's organisation, in order to prevent all competitors from following suit.

What this diagram illustrates is that, at the very least, different perspectives on the future may be imagined. For that reason, the multiplicitous nature of the future should not be underestimated. Even then, executives may be limited by a myopic selection of future options. One way of illustrating such myopia is to distinguish between two foundational forms of decision-making, namely selective versus creative decision-making. In the former, the executive simply selects from the options currently available.

A set of criteria is usually created that form the score-card of the 'best possible' option based on a predefined set of ideal characteristics. This is valuable for highly repetitive operational decisions, but for strategic decisions in a dynamic context such as that faced by the CFO of today, creative decision-making, characterised by innovation, may be more suitable.

In the creative version, options are generated that did not formerly exist. Any conceivable innovation is an example of this approach - it is generative of new possibilities, rather than defensive of previous or current possibilities.

The future is by no means inevitable. No future ever is. It is subject to our collective imagination and design. Executives are therefore advised to make decisions on the likely evolution of a considered bouquet of possible futures, not simply on an extrapolation of the patterns of the past or even on current trends. Once the need to defend the past has been exceeded (and this includes transcending both emotional and specialisation defensiveness), decisions should be made not only FOR the future, but also BASED ON the emerging spectrum of possibility. And this must surpass the current outlook on the future, and should include multiple futures with relative probability, including the decay, mutation or death of current trends and the birth, non-linear development and convergence of yet-unborn opportunities.

The future is by no means inevitable. No future ever is. It is subject to our collective imagination and design. Executives are therefore advised to make decisions on the likely evolution of a considered bouquet of possible futures, not simply on an extrapolation of the patterns of the past or even on current trends. Once the need to defend the past has been exceeded (and this includes transcending both emotional and specialisation defensiveness), decisions should be made not only FOR the future, but also BASED ON the emerging spectrum of possibility. And this must surpass the current outlook on the future, and should include multiple futures with relative probability, including the decay, mutation or death of current trends and the birth, non-linear development and convergence of yet-unborn opportunities.

Metaphorically speaking, it is fair to argue that executive decisions are 'forwards, not options', by which is meant that 'payment' for the decision to obtain the gain or loss will be made at a future time and that the exercising of that right is the compulsory consequence of today's decisions. Given the far-reaching systemic implications of executive decision-making, the intellectual agility to engage simultaneously with multiple possible futures is highly likely to increase as a prerequisite for a chair in the boardroom of the future.